Films

Sat 6th November 1.00am-4.30pm

Training Room 3 (Next to Conference Room)

1st Floor, Imperial War Museum

Lambeth Road SE1

Cy Grant Day at BFI

Sunday 7th November 11am-4pm

BFI SouthBank

Belvedere Road SE1

Tube: Waterloo.

Tickets £5.00 0207 928 3232

www.bfi.org.uk www.blackhistorywalks.co.uk

Cy Grant tribute day

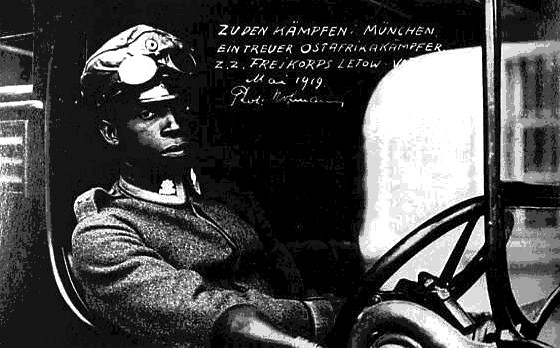

Above: Black Soldier in the German army in Africa World War 1

The Negro Soldier plus Q and A with Jim Pines

Saturday 20th November 2pm-5pm

BFI SouthBank

Belvedere Road SE1

Tube: Waterloo.

Tickets £5.00 0207 928 3232

www.bfi.org.uk www.blackhistorywalks.co.uk

The Negro Soldier (1944), Propaganda and Mobilising African Americans in World War Two

Sections of this Case Study

- Introduction

- Pedagogy

- Details

- Evaluation

- Course Materials

Course Materials

1. Introduction

In early 1944 the United States army showed a new training film, The Negro Soldier, to all black recruits. The military, as well as other sections of government were concerned about the lack of African American's commitment to the war effort. This film, which eulogized black achievement and patriotism, past and present, intended to remedy the situation. Blacks, or Negroes, to use the language of the day, had good reason to feel aggrieved: in the South, where the vast majority lived, they could not vote in elections, and were confined to separate and inferior facilities in public parks, theatres, transport, health and education. Such a system of racial segregation was known as Jim Crow. Indeed, because the armed forces were segregated, black recruits saw The Negro Soldier in all-black theatres, in all-black military units throughout the United States.

The Army's goal in showing the training film was straight forwardly propagandistic in that it wanted to persuade African-American soldiers that their patriotic duty lay in defeating the enemy. We need to ask: how effective was this film in overcoming black soldiers' hostility to life in uniform? While, as we shall see, there is a shortage of reliable evidence to answer this question, one group that effusively welcomed the film was the black middle class. With the support of the film makers, and from within the military, they persuaded the Army to show the film to white soldiers and the civilian population.

Interpreting the meaning and intention of The Negro Soldier cannot be based solely on a reading of a film made so long ago and in another political and social context than our own. To establish meaning and intention we need to closely examine the key groups in the drama of the film's production: an oppressed African American community in the process of rapid change stimulated by the Great Migration northward and World War Two, a black middle class growing in self confidence with its own political agenda, the military with its desire to root out rebellion within its ranks, and the film makers it hired who were skilled in the art of persuasion. However, before examining them in detail, we need to be clearer what we mean by propaganda.

2. Propaganda and Mobilisation

What does it mean to talk of The Negro Soldier as propaganda? Western democracies are uncomfortable with the word, and in popular usage it has pejorative connotations. When asked for examples we invariably look abroad to Nazi Germany and Stalin's Soviet Union where it seems that whole populations were effectively controlled by powerful state media. Social scientists employ the concept more precisely, although even among scholars there is no exact agreement. Most see propaganda as information and ideas disseminated or controlled by government using the mass media, often in times of crisis, to mobilise the populous for a particular course of action. It is not just confined to non fiction media, such as newspapers, documentaries and newsreels, but is also found throughout entertainment.

For propaganda to be effective its purpose needs to be hidden. The state circulates information to its citizens in such a manner that they believe they have been provided with a truthful and unbiased narrative which allows them to make decisions of their own free will. In reality, propaganda's purpose is to mould and sculpt information in such a way as to close down discussion and present one course of action as the natural and obvious choice. Propaganda persuades as much by omission as by distortion. Appeals are made not to intellect and reason but to emotions such as fear, patriotism, the martial spirit, motherhood, and the family. In addition, authority figures are held up, such as gods, or illustrious leaders from the past. Simple messages are presented which make use of easily recognisable national, racial, and gender stereotypes.

During World War Two, Western democracies such as Britain and the United States claimed that their information strategy was the 'propaganda of truth' because it dealt only with facts and avoided lies or unprincipled appeals to emotions. Joseph Goebbels, Nazi minister of propaganda, felt that such a claim was pure hypocrisy. Of course, a subtle approach has the advantage of appearing invisible, so that most of the population would not even know they were being propagandised.

3. African Americans

African Americans were an oppressed people since the foundation of the United States. Until the Civil War (1861-65) most were slaves, but even following the war racial oppression held them in check. By the beginning of the twentieth century this situation began changing as migration drew African Americans from the backward rural South to the urban North. Blacks first filled jobs on a large scale in World War One. The Great Migration, as it has been called, continued throughout the 1920s placing African Americans on the first rung of the occupational ladder working in transport, automobiles, iron and steel and, for women, domestic service. Labour shortages created by World War Two once again stimulated migration, not only northwards but also westwards to the Pacific coast. Now, as a central component of a war economy, black demands for political rights could not easily be shrugged off. In 1941, A. Philip Randolph, a labour leader, socialist, and civil rights activist threatened to lead a march on Washington DC if the US government did not end segregation in war industries and the armed forces. President Roosevelt reluctantly gave ground and opened up a range of relatively well-paid industrial jobs to black men and women. But the armed forces remained resolutely Jim Crow.

Total war not only drew African Americans into civilian employment but also into the military. By war's end about one million African American men and women were members of an armed force of twelve million. The 1940 Selective Service Act banned discrimination in the draft and, as a result, blacks served in all services, although the US Marines only reluctantly dropped its colour bar in 1942. Segregation into white and black units remained throughout the war with most African Americans assigned less prestigious non-combatant support roles. The racial thinking of the army believed African Americans lacked the skills, education, and courage to be effective soldiers.

The war not only intensified long-term economic pressure for black equality by fuelling the Great Migration but also exposed racial fault lines deep within American society. President Roosevelt's lofty declarations of freedom and liberty, something intended for the consumption of those under the enemy yoke, were clearly incompatible with African American's second class status. As the black sociologist Horace Clayton noted the more the 'slogans of democracy' were raised the lower Negro morale sank. (Quoted in Kearney, 108.)

Responding to the wartime rhetoric of freedom and liberty, once in the armed forces black soldiers, embolden by their training and experience of life overseas, objected to their second class status. Some refused to join segregated units declaring that the Selective Service Act expressly forbad discrimination. Most black recruits, even those born in the North, were assigned southern officers and trained in Jim Crow camps in the South where they faced hostility from white authorities who reacted against African Americans in uniform. The Negro soldier's first taste of warfare in World War Two, declared one black officer in 1943, was on army posts right here in his own country. (Quoted in Sitkoff, 668-9.) Army commanders, fearing their black soldiers might take the law into their own hands, restricted the availability of ammunition. In a particular twist of southern racial etiquette, black soldiers escorting German prisoners of war found themselves barred from using the same facilities as their white captives. Going one step further, blood banks, both civilian and military across the country, labelled blood by the race of the donor. As a result, army authorities were constantly worried about the low level of morale as black soldiers went absent without leave, deserted, struck for better pay, and objected to highly dangerous working conditions, most notably following the deaths of over three hundred, ill-trained ammunition handlers at Port Chicago, California, in 1944. Invariably these actions were met with punitive prison sentences and dishonourable discharges. To make matters worse, major race riots broke out in Detroit and Harlem in 1943 sparked off by racial tensions, housing shortages and the social turmoil of the war. Many black soldiers were left wondering why they were fighting for democracy abroad when it did not exist at home, while authorities feared a revolt from within.

African Americans had no illusions about the evils of Nazi racism but found it difficult to endorse the war. According to Adam Clayton Powell Jr, New York Baptist minister, Despite our apathy toward the war, it is not because we don't recognize the monster Hitler. We recognised him immediately, because he is like minor Hitlers here. (Koppes and Black, 385.)

In contrast, many African Americans viewed non-white Japan as their race champions, even though the US was at war with the country since December 1941. For years black intellectuals, such as W.E.B Dubois, had admired Japan's growing strength and its willingness to confront white colonialists in the Far East. US authorities feared the impact of enemy wartime propaganda, which emphasised Japan's affinity with racial-oppressed African Americans. Supporters of Marcus Garvey, and Black Muslims such as Elijah Muhammad, who sympathised with Japan and refused the draft, served prison sentences. Japanese shortwave radio transmissions beamed at African American troops seemed to have made little impact on morale but the army was extremely sensitive to the threat. More alarmingly for the authorities was a 1942 Office of War Information survey of New York City black residents which revealed widespread popular support for Japan. Eighteen per cent believed that they would be better off under Japanese rule, while a further thirty one per cent felt that it would be the same. (Koppes and Black, 386.) In other words, almost half those interviewed believed that rule under the Japanese would be no worse than they currently endured yet all of the respondents would have been aware from the newspapers, radio, and newsreels that Japan stood condemned for launching a cowardly surprise attack on US forces and that the country was engaged in a deadly struggle in the Pacific.

Once America entered the war, all mainstream black leaders dropped their support for Japan, but ordinary African-Americans were not so quick to let go of a vicarious ally. Some black sharecroppers looked forward to the day when conquering Japanese soldiers would sweep away their oppressive southern white landlords. Support for Japan was another way blacks measured their hatred of Jim Crow and was a symptom of deep distrust, cynicism and alienation from American society among poor and desperate peoples.

Leading the battle for African American rights was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Formed in 1909 its goal was legal equality which it fought through the courts, in legislatures and by appeals to government agencies. As a respectable, predominantly black middle-class organisation the Association shunned mass demonstrations and appeals to ordinary African Americans, preferring instead private words with influential whites. The black elite, including those from the NAACP, who were seen as race leaders by government, wanted to seize the political opportunity offered by the war but they also knew that simple appeals to patriotism would anger an already divided and cynical community. Those with longer memories also recalled the broken promises and humiliation following W.E.B Dubois' unconditional support for World War One. The Double V Campaign victory against fascism overseas and racism at home was the black elite's way of mobilising their community for war through a parallel campaign for democratic rights. Even so, the Roosevelt administration took a dim view of the Double V Campaign believing it to be promising only qualified support for the war, and toyed with the idea of prosecuting black journalists who gave it publicity.

African Americans in their bid for social and political justice faced formidable obstacles. Roosevelt's Democratic Party was a coalition of interests which included southern supporters of Jim Crow. Even prior to the outbreak of war, the NAACP had failed to secure a Federal anti-lynching law and now that the administration's attention was focused exclusively on beating the Axis powers the chance of placing black priorities high on the agenda seemed even more remote. Throughout the United States, there was widespread support for segregation; for example, the popular national sport of baseball was organised on racial lines. Children read in their school history textbooks that the American Civil War, which had led to black freedom, was a conflict that should have been avoided, and the subsequent Reconstruction period was inspired by vindictive blacks and their venal northern white allies.

4. Production

The army chose Frank Capra to make its films and lead the Signal Corps' film unit responsible for boosting wartime morale. A successful Hollywood director since the 1930s, and an expert manipulator of human emotions, he was responsible for such films as American Madness (1932), Mr Deeds Goes to Town (1936), and Meet John Doe (1941), where small town values of trust and good neighbourliness offer hope and a way forward to audiences faced with the economic hardship of the Great Depression.

In March 1942, one of the first projects Capra considered was a film dealing with African Americans, but The Negro Soldier, the end result, was not shown to the first batch of new recruits for nearly two years. In part this was a reflection of the army's priorities, but the sensitivity of the subject also created a good deal of internal debate and controversy. Although he claimed credit for the film, Capra's contribution was limited; most of his time was taken up with the much better know seven-part series, Why We Fight. Indeed, it was the early success of these films that encouraged the War Department to create The Negro Soldier. Two months later Marc Connelly was commissioned to write the script, followed later by Ben Hecht and Jo Swerling. But academic experts in the army's Information and Education Department rejected all their dramatisations preferring what they saw as a more modern, factually-based documentary treatment. University social scientists in the Information and Education Department who entered the army during wartime were keen to try out their behavioural psychological techniques through the use of film. As older racial theories of black biological inferiority were discredited so they looked to new ways of motivating African Americans to fight.

In autumn Capra brought in Stuart Heisler to direct the project and, subsequently, Carlton Moss, a black writer and actor, to provide a more authentic screenplay. In January 1943 shooting started and the film crew with Heisler, Moss, and others travelled the country filming African-American soldiers in army bases and training camps.

Carlton Moss was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1909, before subsequently moving to North Carolina and attending what is now Morgan State University, Baltimore, where he formed a troupe of actors who toured black colleges. Subsequently, moving to New York City, he successfully wrote, directed, and acted on stage, wrote his own NBC radio shows, and was a member of the Federal Theater Project in Harlem. Here he was John Houseman's chief assistant for Orson Welles's 1936 all-black MacBeth.

Moss was a product of the growing cultural self confidence of the Harlem Renaissance and the political radicalism of the depressed 1930s. Throughout his life he remained an uncompromising fighter against racism and social injustice and insisted on remaining in the industry on his own terms. Much later, working for Stanley Kramer on the script for Pinky (1949), dealing with the sensitive issue of a black woman passing as white, he refused to portray inter-racial romance as inevitably tragic and was removed from the picture. (Thomas.) As he subsequently recalled, I knew there was no place for me in Hollywood; I could have had a career in the studios after the war, but it was clear that I would have had to make compromises I couldn't accept. (Quoted in McBride, 494.) His reputation as a forthright supporter of black civil rights was so strong that in Home of the Brave (1949), Kramer gave the name Peter Moss, or 'Mossy' to the character of a returning black soldier paralysed from the waist down whose condition is aggravated by a chip on his shoulder about his blackness. This was a sideways complement from a friend but the charge of being over sensitive about race was commonly levelled against blacks who strenuously objected to Jim Crow. In 1951 he was to fall foul of the anti-communist House Un-American Activities Committee, and was barred from earning a living in Hollywood -- the only African American screenwriter on the Blacklist. Moss preferred to earn a living on the edge of the industry making education films with titles such as Healthy Smile and Happy Teeth.

With America's entry into the war, in early 1942 Moss organised his own pageant, Salute to Negro Soldiers, at New York's Apollo Theatre. He was particularly alarmed at the level of pro-Japanese sentiment he experienced in daily conversation with fellow African Americans in Harlem, and by what he felt was the US government's failure to devise a counter strategy. He believed that his play, by highlighting barriers to integration, would undermine black anti-war sentiment and point the way toward better race relations. (Kearney.) It was the success of Salute to Negro Soldiers, and the support of Houseman, that landed Moss the job of screenwriter for The Negro Soldier.

Moss might have thought he could replicate Salute's stage themes on film but the army's requirements and conflict with Frank Capra soon demonstrated otherwise. As Capra later recalled:

Moss wore his blackness as conspicuously as a bandaged head. Time and again he would write a scene, then I'd rewrite it, eliminating the angry fervor. He'd object, and I would explain that when something's red-hot, the blow torch of passion only louses up its glow. We must persuade and convince, not by rage but by reason. (Capra, 358.)

There are no references to racial discrimination in The Negro Soldier, so why didn't Moss, who we know was politically principled and strong-willed, simply walk away from the job? No doubt he felt, like many on the left, that given the priority of the fight against the Nazis that the film was the best that could be achieved; rather than draw attention to issues that were divisive or confrontational it was best to support the war effort and boost black morale by emphasising the positive. As he told a reporter in 1944, his intention was to ignore what's wrong with the army and tell what's right with my people. (McBride, 492.) In the early 1940s Moss was a member of the Communist Party, the most influential political force in leftwing circles in this period. Following the June 1941attack by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union which the Party considered the home of socialism it transformed itself into an enthusiastic supporter of American involvement in the European conflict. Anything that interfered with the war effort, whether it was striking workers in war industries or militant support for black civil rights, was condemned by the now ultrapatriotic Party. James Ford, a leading black Communist, declared that while the Party would continue to oppose segregation in the military it would be equally wrong to press these demands without regard to the main task of the destruction of Hitler, without which no serious fight for Negro rights is possible. (Quoted in Isserman, 119.) Communists did not give up the struggle for black equality during the war, as their enemies charged, they did push for black rights in areas considered beneficial to the war effort, but for the time being fighting fascism was a higher priority than fighting Jim Crow.

The film that Heisler, Moss, and Capra created is not what we see today as the Army insisted on cuts. It was worried that the film would upset the existing racial order by creating an unrealistic level of expectation among black Americans, and deep hostility from white recruits. Blacks, the Army feared, would take the representation of African Americans in combat at face value and insist that reality match up to propaganda, while whites might resent blacks' improved image. Cut sequences showed blacks being led by black officers, blacks in combat, and a scene where a white female nurse treats a black soldier. All transgressed prevailing Jim Crow policy (although it was Army practice for white medical staff to administer to black soldiers). Even as the final version was agreed in January 1944, conservative elements within the Army tried unsuccessfully to restrict the film's use.

5. The Negro Soldier

|

Viewing and Questioning Before seeing the film you should note down the questions you want answers to. Here are some you may want to think about:

|

The forty-three minute film opens among a comfortable middle-class black congregation in a striking Gothic church set in a northern city. The beautiful voices of the soloist and choir swell to a finale while in the congregation are well dressed and respectable men and women, some in the uniforms of the armed forces. A handsome young preacher, played by Carlton Moss, begins by identifying some of those in uniform, including 'Private Parks First Class', an attractive light-skinned member of the Women's Army Corps. The preacher, who is our guide throughout, puts aside his prepared sermon and turns his attention to persuading the congregation that having achieved so much by American birth it should redouble its efforts to defeat the enemy.

The sermon divides into six segments. In segment one, the preacher draws attention to past black achievements. He recalls the Joe Louis versus Max Schmeling boxing match for the heavyweight championship of the world. Here the congregation is told that 'An American fist won a victory', and that the present conflict is not a game but a fight for the real championship of the world. Quoting from Adolph Hitler's memoir, Mein Kampf (1925-6), the pastor highlights Nazi beliefs in African American racial inferiority blacks are half ape and their ruthless expansionism, and contrasts this with American commitment to liberty.

Segment two draws attention to black involvement in America's military conflicts from the Revolution, War of 1812, Civil War, Spanish-American War, to World War One. In addition, African Americans are seen as participants in creating a new nation as western pioneers, and builders of railroads, factories, and cities.

Past achievements merge, in segment three, into recognition of the more recent accomplishments of black leaders Booker T Washington, George Washington Carver, and those building the monuments of tomorrow in the fields of law, medicine, education, business, entertainment, and the arts. Here we also see footage of the 1936 Berlin Olympics and black achievement in sprinting and high jump. The pastor reminds his congregation that the tree of liberty has borne these fruits of African American success.

Segment four draws attention to the crimes of the Nazis and Japanese and their lack of commitment to liberty. We see German aerial bombing, hanging of innocent civilians, and the enslavement of 150 million Europeans. The terrible consequences of Japanese terror bombing of Chinese cities are graphically portrayed with corpses loaded onto to carts being hauled away.

In segment five the pastor is interrupted by Mrs Bronson, a handsome woman with a fashionable fur stole over a well tailored suit who reads from a letter she has received from Robert, her son, telling of his experience as an Army recruit. There is hardship in parting, confusing parade-ground drill, unfamiliar clothing, strict instructions on bed making and how to salute properly, sleep deprivation, cross-country marches, and shooting practice. But not everything is tough: there are sporting events, poetry reading, Saturday night dances where Robert meets an 'apple pie' girl, and Sunday church services. Even more important, we are told that Robert, like many black soldiers of his generation, is doing well and will shortly be entering officer training school. After that he will be ready to get in there and get this war over with.

The sixth and final segment looks beyond Robert's experience to highlight the variety of roles performed by blacks in the armed forces. We see clips of Tuskegee airmen, tank crews, quartermasters, infantry, and engineers in training. With the shadow of defeat hanging over the Axis partners the preacher insists that these toughened black soldiers must not let up the fight. The pastor concludes by reminding the congregation of those African Americans who have died in the present conflict defending their land of birth. A medley of religious and patriotic music swells with a final 'V' appearing superimposed over the Liberty Bell.

6. Assessment

The Negro Soldier provides audiences with a glowing picture of African American wartime life and achievements. Just like white America, blacks are seen as patriots fighting in earlier conflicts and pioneer builders of a new nation. At the same time, we are told that readily available opportunities encourage African Americans to excel in business, the professions and the arts. In the present conflict, African Americans are portrayed as fighting and dying alongside white Americans, while men of the calibre of Robert Bronson are destined for the ranks of the officer corps. But such a portrait can only be painted by seriously distorting the historical and contemporary record of black life.

Vast areas of African American experience which run counter to the optimism of the film are simply omitted. There is no mention of slavery (only German enslavement of conquered Europeans), the struggle for emancipation, late nineteenth-century disfranchisement, Jim Crow racial segregation, lynching (a practice continuing in the South), the economic exploitation of sharecropping, northern pogroms against new arrivals, and black and white attempts to combat racism and built a multi-racial society. Jim Crow and Army segregation are presented as unremarkable parts of everyday life.

The class bias of The Negro Soldier is relentless in its portrayal of black life as exclusively middle class. Such a narrow and distorted view serves an important purpose in conveying the Army's intended message of black achievement while, at the same time, helping allay possible fears on the part of white middle-class America. The vast majority of African Americans, as share croppers, landless labourers, factory hands, and domestic servants, and their achievements under adversity, are airbrushed out of the picture. Instead we see a comfortable, middle-class congregation set in a northern city. But this congregation is far from a typical gathering of African Americans, the great majority of whom were southern, rural and poor. The congregation we see behaves in a dignified and restrained manner with none of the emotional exuberance of lower-class church services, while the preacher points to financiers, doctors, judges, school principal, and orchestra conductors as examples of black success.

Robert Bronson's experience is exceptional: the Army commissioned only a few thousand African Americans; most blacks were officered by whites and strict racial hierarchy prevented blacks taking charge of white troops. Although the film portrays recruits in combat training prevailing racial stereotypes considered blacks temperamentally unsuited to fighting thus consigning them to behind-the-lines support roles.

While African Americans are presented in the film as 'me too' patriots fighting alongside whites, blacks, because of their second class status, possessed a more complex and ambivalent attitude toward America's wars. In the Revolution, rather than fight on the side of the colonists, large numbers of slaves took the opportunity to runaway from their American masters eventually sailing away with the British. For the first two years of the Civil War, northern free blacks refused involvement, calling it a white man's war, because Union military goals extended no further than returning errant southern rebels to the national fold. Only when President Lincoln announced the ending of slavery did blacks flock to the colours. While the black veterans of World War One, fighting to save democracy in France, shown in a victory parade, soon heard feet of a different kind as the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan marched through the streets of their home towns and in the national capital, Washington, DC.

The Negro Soldier portrays both major wartime protagonists, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, but the film is hardest hitting in its treatment of the Nazis. The Japanese, in contrast, are given a lighter touch since the Army did not want to antagonise African American audience known to be sympathetic to the Japanese. Sinister music strikes up as the swastika is displayed and we are shown examples of Nazi atrocities and the spiteful destruction of a monument to black soldiers' valour. At the same time black American victories over Germans are highlighted with Jesse Owens' athletic triumph at the Berlin Olympics and Schmeling's defeat at the hands of Joe Louis. The portrayal of the Japanese is muted and the propaganda approach more restrained. In the one scene of Japanese atrocities the voice-over of the preacher simply asserts: There are those who tell you that Japan is the saviour of the colored races. Here, in the most subtle fashion, Japanese claim of solidarity with other coloured peoples is simply and fatally undermined. The film makers knew that to try to enlist the sympathy of black audiences with tales of Japanese ill treatment of (white) allied prisoners of war would miss the mark.

How do we assess the impact of the film upon black soldiers, the African American community, and wider American society? Remember, our reading of the film is tempered by the fact that most of us have never experienced Jim Crow or world war. We are located in the twenty-first century, well after the tumultuous events of the Civil Rights era of the 1960s when African Americans regained the right to vote in the South, but we still live in a world disfigured by racism. All of this will make our assessment of the film different from that of American wartime audiences. As a result, to make a rounded judgement we also need to look at evidence that lies outside of the film.

James Agee, journalist and influential critic writing in The Nation, thought that the film would matter a good deal to black soldiers, but just how African Americans in uniform responded is difficult to gauge since they saw the film on military bases under Army discipline. (Agee.) Another film critic, John McManus, recounted a story told to him, 'umpteenth hand, of course', in which cynical black troops when shown the film are persuaded by its message and, as the screen fades, leap to their feet, snap to attention and salute. (McManus. Film Review.) It could be true, no doubt many soldiers reacted positively, but there is a neatness to this tale that suggests it was first circulated by the Army, or other government source, which we know expressed concern lest the film be dismissed by enlistees as nothing more than propaganda. Of course, showing the film might reduce the likelihood of serious revolt but so long as the cause of friction remained Army racial segregation and black trainees chafing at Jim Crow restrictions around southern bases then it is no surprise that reports of poor morale among black troops continued to circulate.

The opinion of major newspapers was mixed. Bosley Crowther, the well know movie critic of the New York Times, noted the educative value of the film to white audiences but felt that its serious omissions would reduce its effectiveness among those fully aware of segregation's extent. (Crowther.) The movie theatre trade paper, the Motion Picture Herald, judged the film a competent job, dramatically and emotionally effective. The educative purposes of the film have been furthered by good photography, a nice variety of scene, some flashes of humour and excellent musical background. ('Negro Soldier.')

The film was originally intended only for black military recruits but under pressure from the NAACP, supported by social scientists in the Information and Education Department, the Army agreed to show it to white military trainees. In April the Office of War Information made the film freely available to commercial movie theatres throughout the country. But few actually saw the film in theatres: of the over 16,000 theatres in the country only 1,819 requested the film. In contrast, Memphis Belle, another government-made film, recounting the exploits of a white bomber crew which was released in the same year, was seen in over 12,000 theatres. To improve its prospects The Negro Soldier was shortened to half its length allowing it to appear with a feature film as part of a full programme. Carlton Moss estimated that the shorter film was seen in 5,000 commercial theatres, mostly by whites. But it probably did even better after April 1944 when it was distributed non-theatrically to public libraries, schools, colleges, and black and white church groups. According to one estimate, during the second half of 1944, approximately 3.1 million people saw the film. (Kryder, Divided Arsenal, 156.)

But, whatever the opinion of critics or the actual size of the audience, it needs to be remembered that the film was one small wartime voice in an otherwise uninterested or hostile media environment. The Negro Soldier was the most successful of only a tiny handful of government films, which included Wings for this Man (1945), and The Negro Sailor (1945), where honest, competent and intelligent African Americans appear centre stage. At the same time Hollywood continued to produce feature films to a mass market that largely ignored the problems of race and African Americans. Films such as Bataan (1943) and Sahara (1943), while they portray black characters as members of integrated units, are misleading exceptions to the rule. A study by Columbia University in 1945 found that of one hundred black appearances in wartime films, seventy five perpetuated old stereotypes, thirteen were neutral, and only twelve positive. (Koppes and Black, 404.)

Given the short-comings of the film, it may seem surprising that it was among the black middle class that the response to The Negro Soldier was most positive. In January 1944, two hundred black journalists were invited to a formal screening at the Pentagon where Frank Capra introduced the new film. Moss and Heisler, though, had already alerted black leaders to the political opportunities offered by the film with a private showing in Harlem. The Army was caught in a trap, recalled Moss, the film could not be tampered with. And they were smart enough to see that everybody had got what he wanted. (Quoted in McBride, 494.) Reviews in the black press were ecstatic and the NAACP took over promoting the film as its own, even though it had no involvement with production.

It is not difficult to see why the black middle class was favourably impressed by the film. Long traduced by filmic stereotypes of happy go lucky blacks as servants, comedians, chicken thieves, superstitious believers in ghosts and possessors of a simple childlike religion, here was a film with Hollywood production values that treated blacks seriously. Adopted as their film by the black intelligentsia, - patriotic, opportunistic and politically cautious The Negro Soldier became a blueprint for a racially integrated world full of material opportunity. They saw on screen, in the church congregation, images of themselves which they absolutely endorsed. What role the mass of lower-class African Americans had to play in the unfolding drama of black emancipation remains unclear. As Thomas Cripps and David Culbert point out, the Army intended making a propaganda film that would stimulate patriotism and boost morale, without threatening the existing Jim Crow racial order. But the Army found itself in a bind: to assuage black aspiration and to avoid troops simply dismissing the film as crude propaganda, The Negro Soldier was forced to paint a picture of black life far more glowing than existed in reality. Such a picture unintentionally undermined segregation. Black leaders took this picture as a statement of government intention. 'Who would have thought that the Army, officially committed to segregation, would end up with a film which symbolically promoted the logic of integration?' asks Thomas Cripps and David Culbert, 'Who would have thought that a military orientation film would make black civilians glow with pride?' (Cripps and Culbert, 133.)

The Army intended the film would transform black dissatisfaction into wholehearted support for the war. Promising unbelievable opportunities, silent on the question of segregation, The Negro Soldier supported winning the war above all other goals. Nevertheless, some of those in the theatre refused to read it in quite that fashion and instead took it to mean government endorsement of black progress. While we might consider The Negro Soldier an example of powerful and effective government propaganda, a section of the audience, drawing upon their own needs and political aspirations, re-appropriated the film's message.

At the same time as the NAACP promoted The Negro Soldier it actively undermined a rival commercial production, We've Come a Long, Long Way (1944). Covering much the same ground as the government's film, We've Come a Long, Long Way, which received a 1943 Academy award nomination for best documentary feature, highlighted a black preacher, warned of Nazi and Japanese domination, traced the progress of African Americans using newsreel clips, and included contributions from the president of the National Council of Negro Women, and a banker and former college president. The film was narrated by the well-known radio evangelist, Elder Lightfoot Solomon Michaux and included footage of George Washington Carver, Joe Louis, Paul Robeson, Lena Horne and Bill Robinson. (At the World.) The producer, Jack Goldberg, had long been involved in making low-budget films, pejoratively referred to as 'race movies', featuring black casts and intended for poorer African American audiences. He sued the government in Federal court rightly claiming that releasing The Negro Soldier without charge to theatres, undermined the profitability of his production. The NAACP successfully intervened in the legal proceedings to support the government, and undermine Goldberg's reputation in the Jewish community by accusing him of being an exploiter of black audiences.

At a time when there were few celluloid images of African Americans it may seem puzzling that the NAACP should deliberately sabotage a worthwhile movie that placed African Americans centre stage. Yet the reason is clear enough, NAACP political strategy looked to government for assistance; The Negro Soldier spoke with an officially voice carrying with it the aspirations of African Americans. In the eyes of the NAACP, race movies were cheap, unsophisticated and unwholesome fare for lower-class blacks, unsuited to the self-image of the urban black middle class.

Army segregation and Jim Crow both eventually disappeared and with it went the need for such films as The Negro Soldier. The Korean War, 1950-53, was the military's first conflict as an integrated force. Long-term social change unleashed by the Great Migration and amplified by the political and ideological impact of World War Two and Nazi extermination policies made it difficult to hold African Americans as second-class citizens; the Cold War battle for the hearts and minds of the Third World completed the process. As southern blacks gained the vote under the impact of the Civil Rights movement so the Old South of Jim Crow ceased to exist.

However effective we judge government propaganda to be in mobilising blacks for the war effort, it is clear from this account that propaganda is not omnipotent, and that the relationship between propaganda and society is more complex than our earlier and simple model suggests. It is difficult for propaganda to deny entirely material reality. Audiences draw upon their own experiences which confirm, deny, or subvert on-screen messages. Black recruits may have been willing to accept many of the ideas of The Negro Soldier but a meal eaten in a segregated canteen or a brush with the police following a trip off base might force a reappraisal. At the same time, because the black middle class rejected the racial conservatism of the film and adopted it as an anthem to their emancipation, we need to recognise that propaganda can have unintended outcomes. The black community, faced with the immense task of ending segregation, was not a homogenous group but riven with cultural and class differences which encouraged blacks to interpret and appropriate ideas in ways not necessarily intended by the propagandists.

From http://www.filmandsound.ac.uk/support/learning/casestudies/negrosoldier/materials.shtml

Sunday 28th November 3.00-7.00pm prompt start

Venue: Stonebridge Hillside Hub, 6 Hillside, London NW10 3NB

Tube: Harlesden/Stonebridge Park on Bakerloo Line (10 mins walk)

Bus: 18, 206, 266, 260, PR2

Admission: £6.00 per person, first come first served pay on the door

The original 3.5 hour event comes to North London.

African Superheroes: Many artists are making up for the severe lack of positive images of black people in animated films and comics. This animation festival for 6-60 year olds, will feature a variety of African-themed cartoons which tell tales of; Magical Nigerian women warriors, Anansi the West African Folk Hero, The story of Ogun and Oshun, Teenage black superheroes and more